My home town once boasted fifteen schoolhouses that were built between the end of the Civil War and 1899. All but the high school were named for presidents of the United States: Adams, Buchanan, Fillmore, Harrison, Jackson, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Pierce, Polk, Taylor, Tyler, Van Buren, and Washington. Another of their ilk came along in the early 1900s; Lincoln was its name.

With the Adams School counting for two presidents — the second and sixth — there was a school for every president through Lincoln. Why Lincoln came late is a mystery to me. Lincoln was revered by us Northerners, and his picture was displayed proudly next to Washington’s in schools and municipal offices. We even celebrated Lincoln’s Birthday as a holiday distinct from Washington’s Birthday (a.k.a. President’s Day).

More schools — some named for presidents — followed well into the 20th century, but only the fifteen that I’ve named were built in the style of the classic red-brick schoolhouse: two stories, a center hall, imposing staircase, tall windows, steep roof, and often a tower for the bell that the janitor rang to summon neighborhood children to school. (The Lincoln, as a latecomer, was L-shaped rather than boxy, but it was otherwise a classic red-brick schoolhouse, replete with a prominent bell tower.)

I attended three of the fifteen red-brick schoolhouses. My first was Polk School, where I began kindergarten two days after the formal surrender of Japan on September 2, 1945.

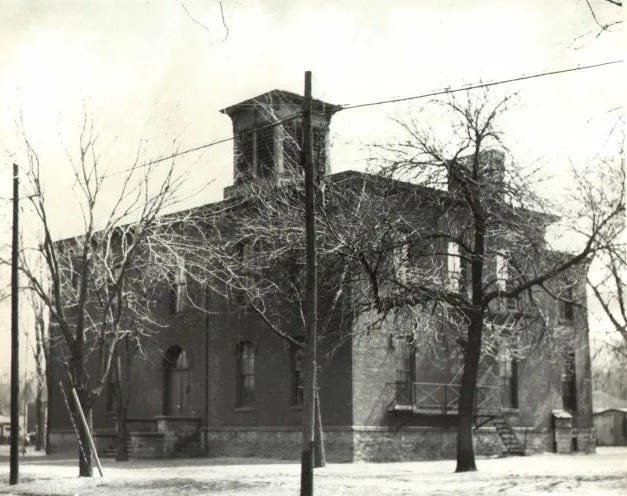

Here’s the Polk in its heyday:

Kindergarten convened in a ground-floor room at the back of the school, facing what seemed then like a large playground, with room for a softball field. The houses at the far end of the field would have been easy targets for adult players, but it would have been a rare feat for a student to hit one over the fence that separated the playground from the houses.

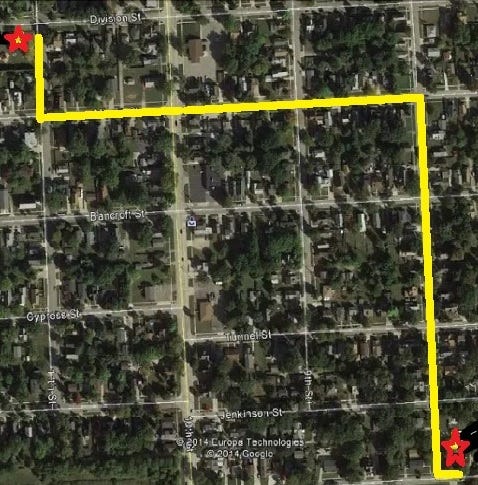

In those innocent days, school-children in our small city got to school and back home by walking. Here’s the route that I followed as a kindergartener:

A kindergartener walking several blocks between home and school, usually alone most of the way? Unheard of today, it seems. But in those days predators were almost unheard of. And, as a practical matter, most families had only one car, which the working (outside-the-home) parent (then known as the father and head-of-household) used on weekdays for travel to and from his job. Moreover, the exercise of walking as much as a mile each way was considered good for growing children — and it was.

The route between my home and Polk School was 0.6 mile in length, and it crossed one busy street. Along that street were designated crossing points, at which stood Safety Patrol Boys, usually 6th-graders, who ensured that students crossed only when it was safe to do so. They didn’t stand in the street and stop oncoming traffic; they simply judged when students could safely cross, and gave them the “green light” by blowing a whistle. In the several years of my elementary-school career, I never saw or heard of a close call, let alone an injury or a fatality.

I began at Polk School because the school closest to my home, Madison School, didn’t have kindergarten. I went Madison for 1st grade. It was a gloomy pile:

Madison was shuttered after my year there, so I returned to Polk for 2nd and 3rd grades. Madison stood empty for a few years, and was razed in the late 1940s or early 1950s. Polk was shuttered sometime in the 1950s, and eventually was razed after being used for many years as a school-district warehouse.

The former site of Madison School now hosts “affordable housing”:

There’s a public playground where Polk School stood:

I spent two more years — 4th and 5th grades — in another red-brick schoolhouse: Tyler School. It’s still there, though it hasn’t been used as a school for many decades. It has served as an apartment house and a halfway house for addicts. It now looks like this:

The only other survivor among the fifteen red-brick schoolhouses is Monroe School, which now seems to serve as an apartment building:

Tyler and Monroe Schools are ghosts from America’s past — a past that’s irretrievable. It was a time of innocence, when America’s wars were fought to victory; when children could safely roam; when marriage was between man and woman, and usually for life; when deviant behavior was discouraged, not “celebrated”; when a high-school diploma and four-year degree meant something, and were worth something; when the state wasn’t the enemy of the church; when politics didn’t intrude into science; when people resorted to government in desperation, not out of habit; and when people had real friends, not Facebook “friends.”